The Roleplaying Origins of Early Dungeons and Dragons

Classic modules show early editions centered on negotiation and player ingenuity, contrasting with later skill-driven, performative approaches.

There’s a common misconception floating around that narrative roleplaying in tabletop games is a relatively modern invention, something that only came into focus with the later editions of Dungeons & Dragons and other game systems like Blades in the Dark. This belief, while understandable, couldn’t be further from the truth. From its earliest days, DnD was designed with roleplaying at its core—a distinction that set it apart from the wargames that preceded it. Sure, early DnD had its share of combat (often brutal and unforgiving), but if you think it was all about kicking down doors and hacking away at monsters, you’ve missed the point, and probably rolled a lot of new characters. The truth is, combat was risky, and survival often depended on players being more thoughtful, more cunning. Roleplaying wasn’t an option; it was a necessity, at least in the way early DnD framed it but more on that later. Many of the early modules assumed players would be talking, negotiating, and thinking their way out of danger as often than they’d be fighting.

The Assumptions Behind Early Roleplaying#

Modern gamers didn’t invent roleplaying—they inherited it. However, it’s fair to say that what we now consider “roleplaying” has evolved significantly since the earliest days of DnD. Back then, roleplaying was less about theatrical performance and more about practical problem-solving and character goals. The roots of DnD in wargaming meant that much of the roleplaying was centered around diplomacy, negotiation, and building relationships—things that didn’t need a lot of rules because the system trusted players to bring their own creativity to the table.

Characters in early DnD didn’t have a list of skills to guide them. They didn’t have a “persuasion” or "Insight" roll to determine if they could talk their way out of trouble or detect lies. The system didn’t do the thinking for the player. Instead, it was up to the players to decide what their characters would do in any given situation. Want to negotiate a truce between two warring factions? That’s on you, the player, to figure out. The DM was there to adjudicate the outcome, but the process was driven entirely by the player’s ideas and actions. This was a FEATURE of the early game design and one of the reasons I find games with an OG design philosophy like Shadowdark so compelling. I think others do as well, which is why there is such an explosion of OSR games, each with it's own community and appeal.

Skills were not included in these early editions because it was assumed the characters thoughts, talents, goals, and decisions were entirely the domain of the player, with help from the DM to fit them to the setting. This was not seen as the domain of the rules, and some can credibly argue that the introduction of skills deminished that. More on that below.

Examples of Roleplaying in Early DnD Adventure Modules#

As proof, I offer you the early classic adventures of B/X and AD&D, where roleplaying and negotiation were front and center:

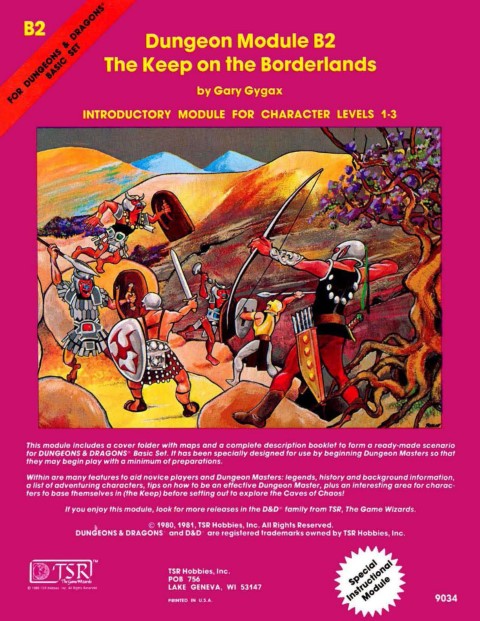

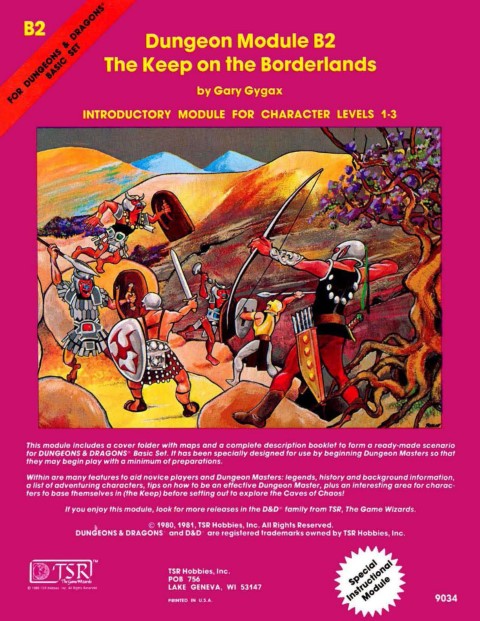

B2: The Keep on the Borderlands (1979): Here, the Caves of Chaos are populated by various humanoid tribes, and players are encouraged to negotiate or manipulate these groups. Forming alliances wasn’t just possible—it was an assumed strategy for success. I know this module was selected as the basis for the new DnD 2024 Starter Kit and I don't think it was an accident. I expect the negotiation and roleplaying elements are a big part of why this selected.

T1: The Village of Hommlet (1979): The village itself is teeming with NPCs who have their own motivations and secrets. The players are expected to engage with these NPCs, gather information, and solve the underlying mysteries—diplomacy and social interaction were key.

X1: The Isle of Dread (1981): This module blends exploration with opportunities for diplomacy. Players can negotiate with native factions, and how they handle these interactions can dramatically affect their survival.

I1: Dwellers of the Forbidden City (1981): The Forbidden City is a complex environment where factions vie for power. Players can navigate this web of intrigue through negotiation, making roleplaying a crucial component of the adventure.

L1: The Secret of Bone Hill (1981): Restenford, the town featured in this module, is a hotbed of NPC interaction. Players are encouraged to investigate and solve local mysteries by engaging with the townsfolk—again, roleplaying takes the lead.

A1: Slave Pits of the Undercity (1980): Although this series is known for its combat, A1 offers opportunities for infiltration, negotiation, and deception. Players can choose to engage slavers diplomatically, leveraging social skills over combat.

C1: The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan (1980): Survival in this module often hinges on the players’ ability to think creatively and roleplay effectively. It’s not just about fighting—it’s about engaging with the world in a way that bypasses danger. This is perfect as a "survival and planning as roleplaying" type of module where action isn't just funny quips and voices.

S1: Tomb of Horrors (1978): This infamous module is packed with deadly traps, but it also demands intellectual engagement. Players must decipher clues and solve puzzles through roleplaying and creative thinking. So even the glassic "meat grinder" module itself, at least assumed a heavy amount of though from the point of view of the character. Again, roleplaying isn't just about what a character says, it's about what a character thinks and why.

B3: Palace of the Silver Princess (1981): The palace is home to various factions, and players can navigate the adventure through diplomacy and alliance-building. Roleplaying is essential to making it through this module.

These examples make it clear: Roleplaying wasn’t just an optional extra in early DnD—it was baked into the design. The game expected players to engage with the world and its inhabitants in dynamic, creative ways, using their characters’ social skills just as much as their swords.

Something Gained and Something Lost#

As DnD and TTRPGs have evolved, we’ve gained a lot in terms of narrative depth and character development. Today’s games often put a stronger emphasis on storytelling, character backstories, and interpersonal dynamics. This shift towards a more narrative-driven form of roleplaying has brought a richness and emotional depth that I personally enjoy.

But is it better? It’s hard to say. On one hand, the theatricality of modern roleplaying can be incredibly rewarding when done right, creating immersive and memorable experiences. On the other hand, it’s fair to acknowledge that this shift has come with some trade-offs. The rise of skill rolls and predefined abilities has made problem-solving more about mechanics than player creativity. In the early days, the game required players to think, plan, and strategize their way through challenges, often through group discussion and collective decision-making. Today, roleplaying can sometimes feel more like a series of individual performances rather than a collaborative effort.

Conclusion#

I’m not saying one way is better than the other, but I do think we’ve lost sight of some of the core elements that made early DnD what it was. Roleplaying was always a central pillar of the game, and it didn’t need the elaborate systems we see today. Instead, it relied on the players’ own ingenuity and the social dynamic at the table. In moving towards a more performative style of roleplaying, we’ve gained a lot, but we’ve also left something behind. It’s worth remembering that the strategic, puzzle-solving aspect of the game—the part where players had to think their way through a problem—was just as important as the roleplaying itself. And in losing that, we may have lost a bit of the magic that made the early game so special.

Drop a comment on X and let me know your thoughts!